Logistics and Crisis: The supply chain system in the Po valley region

a critical overview by Niccolò Cuppini, Mattia Frapporti, Floriano Milesi, Luca Padova, Maurilio Pirone

Bologna, Italy

First, we provide some profiles of what logistics is and why it is so crucial nowadays. From a theoretical point of view, we are prompted by the second book of Capital by Karl Marx. There, Marx discerns between the ‘productive time’ and ‘circulatory time’ of commodities. According to Marx, capitalist production needs to reduce the circulatory time of commodities (the so-called ‘turnover time’) as much as possible, because during that period the capitalist cannot convert so-called surplus-value into profit. For these reasons, from the capitalist point of view, it is so important to have a ‘turnover time’ that is close to zero. Therefore, it is decisive to have an efficient logistics plan. The more the whole world has become globalized, the more logistics has acquired importance. Now it has a lead role in what Anna Tsing calls, ‘supply chain capitalism’. We see how many commodities cross logistics centers before arriving in Europe and how many people work in this branch. We can also see how crisis exacerbates the precarious conditions in which logistics workers have had to work. For sure, logistics workers have had to face precarious working conditions for many years, but following the crisis their job has become even more central because of the cutbacks on expenditure that many multinational corporations (like TNT, Amazon, Ikea and others) have made in order to maximize their profit.

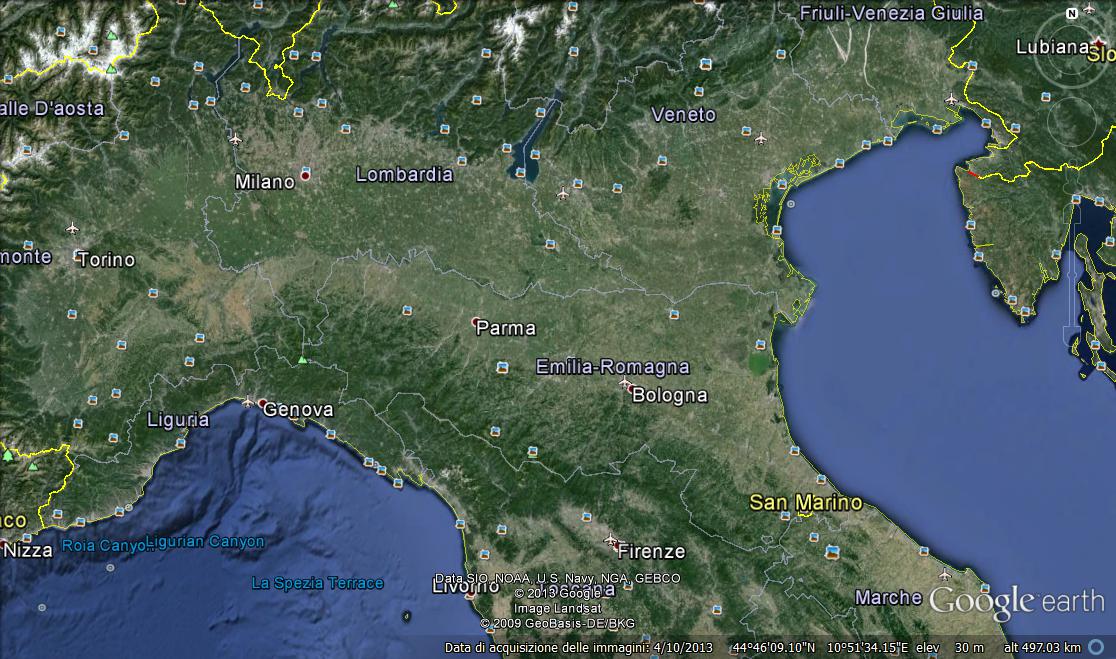

After a general overview of the phenomenon, we will try to climb down a geographical scale aiming to show – by way of a snap-shot – the concrete implementation points of some global flows of goods and people. In other words, by rehearsing a cartographical rhapsody of the logistical supply chain in northern Italy, we will talk about logistics as a political apparatus of production with its own spatial dimensions. We see the Po valley as a specific place of political spatialization that contains forms of territorialization and de-territorialization. In this context, logistics plays a role as a vector that charts the fading of ‘traditional’ political forms (state, cities, regions and so forth). Logistics is shaping new territories into a widespread metropolis conforming to the structure of capitalistic organization. The geographies of urbanization which have long been understood in the Po valley with reference to densely concentrated populations and an older framing of city-scapes, are assuming new and increasingly large-scale morphologies that, as Neil Brenner has said, “perforate, crosscut, and ultimately explode the erstwhile urban/rural divide”. Logistics is generating new types of bordered spaces that cut across traditional inter-state borders and help to give the category of territory/region a measure of conceptual autonomy form the nation-state. This is a territory that deborders territoriality as a political technology that has both spatial and non-spatial elements. A territory developed through networks and assemblages, not only with the tools and rationality of capital accumulation, but also through the processes of strikes, struggles, conflicts. A non-linear geography arranged principally of road transport hubs and warehouses that seem like kinds of contemporary harbours. These are some of the principal strategic places that constitute the focus of this research: the organizational and conflictual experiences in the logistics supply chain and their ability to read, reinterpret and shape the territories from below and drawn by the circuits of commodity mobility. This is the scenario. Shifting to this perspective, we can see a double map of the Po valley region that shows logistics as a biopolitical technology in its deep ambivalence: its centrality in managing the movements of labor and commodities that connect the transnational level with the local, transforming the territory by breaking the traditional political borders; the experimentation of overturning the dense network of lines of production connecting hubs and warehouses in the Po valley and opening it up towards northern Europe and the Mediterranean. At the very least, logistics’ routes are tracing new forms in the organization of space.

The next step of this research highlights the organization of labor inside the system of logistics in Emilia-Romagna. In fact, in this region, cooperatives have been one of the most fundamental institutions of production and as a model have also been introduced into the system of logistics. First of all, we will explain what a cooperative is. There are two general principles that make it different from a conventional business: a mutualist purpose and democratic control. Second, we will conduct a brief excursion into the origins of the cooperative movement, above all pointing out its workers roots. Based on the ideas of the so-called ‘utopian socialists’, cooperation developed as a form of solidarity and organization between workers in response to the social conditions of Industrial Revolution. The idea was to engage in a market economy without exploitation and, in time, it became a non-conflictual instrument through which the subaltern classes were included in economic development. Third, we will show how this form of workers organization has been exploited in the logistics sector in order to maximize profits. Having lost the original spirit of solidarity, nowadays cooperatives are mostly an instrument to manage a low-cost and highly-exploited labor-force: many enterprises decided to outsource their logistic services to a set of co-operatives because of their flexibility. In fact we can note the existence of a system of co-operatives, a vertical organization between enterprises and cooperatives whose aim is to reduce costs and to split and dispel responsibilities.

Subsequently, we intend to investigate the role of trade unions in the logistics sector. First, we provide an overview of rank and file trade unions that are more established in the logistics sector than big (or confederate) unions. The term ‘rank and file unions’ includes all of those conflicting unions that present themselves as alternatives to the bigger unions. Second, we will look at the relationship between unions and migrant labor. The wide-spread presence of migrant workers, especially in the warehousing industry, raises some questions about the aims and the processes of industrial action. In most cases, unions treat migrants the same as all others workers without recognizing the specificity of migration laws such as the ‘Bossi-Fini Law’. The ‘Bossi-Fini Law’ is a way to regulate the organization of labor. For the most part, unions think that migrants just need some specific integration policies, refusing to acknowledge their centrality in struggles. Third, we focus on the rank and file trade union SI COBAS and its leading role in the struggle for fair salaries and the rights of logistic workers. Starting from this case, we show that unions still have an important tactical function in workers struggles despite their organizational and political limits.

In the final section of this research, we analyze the impact of the crisis from the point of view of its social subjects. In a wide and complex process of production, the crisis has a different impact on the different subjects involved and is influenced by gender and by social and cultural differences. In front at the gates of factories and warehouses during the mobilizations of logistics workers. we encountered different points of view criss-crossed by different biographies and motivations. The crisis was mentioned often and seemed like a threatening ghost influencing these subjects from ‘behind a curtain’. Following our field work and engagement in this context, a good path seems to be to interview the actors about the different facets of the crisis. Does the crisis affect everyone? Is the crisis an instrument used to worsen the conditions for workers? Is the crisis an inescapable destiny? We will develop questions that try to understand and reveal how the subjects involved read their context and read themselves within a process that is geographically wide and historically deep.